Collaboration and innovation are helping the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, tackle some of the region’s top health challenges, from opioid use disorder to Type 2 diabetes.

UT researchers and their community partners are working together to address health disparities in rural Appalachia and in other underserved communities. These programs are rooted in implementation science: the process of applying research findings and evidence-based practices to improve the quality and effectiveness of health care services.

COURAGE Reaches Rural Counties

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Tennessee ranked third in the nation for drug overdose deaths in 2022. UT is working in Tennessee communities to help reduce addiction and improve the lives of those affected by substance use.

To address opioid use disorder, UT faculty, staff, and students participate in the East Tennessee Rural Health Consortium, a 50-member coalition of government and private agencies committed to reducing OUD and overdose deaths. The consortium is changing the lives of individuals and communities through the coordinated delivery of prevention, treatment, and recovery services to those affected by addiction.

The consortium’s project Combating Opioid Use in Rural Appalachia with Grace and Evidence, or COURAGE, is supported by the US Health Resources and Services Administration. It brings together consortium members from UT Knoxville; the UT Health Science Center; ICARE–Union County; Live Free Claiborne; the Hill Church in Tazewell, Tennessee; First United Methodist Church of Newport, Tennessee; and Broadway and Main Pharmacy of Newport to accomplish five goals:

- Train East Tennessee college students who are studying to be physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners to care for patients with OUD

- Reduce the stigma toward people who are prescribed OUD medications as part of their recovery

- Educate rural fifth graders and the adults who care for them about OUD and its prevention

- Equip faith community leaders with the knowledge to support people with addiction and their families

- Coordinate drug take-back initiatives to collect unused and no-longer-needed medications

College Students Get Firsthand Experience

Under COURAGE, nurse practitioner students from UT Knoxville join students from East Tennessee State University’s Quillen College of Medicine and Lincoln Memorial University’s Physician Assistant Program to work with patients at addiction treatment providers.

Jennifer Tourville

“Students are learning how to talk to those who have a substance use disorder,” said Jennifer Tourville, executive director for the UT Institute for Public Service SMART Initiative, who oversees COURAGE’s Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Mentoring Program. “They are learning how to ask questions like ‘How’s your mental health?’ and ‘What drugs have you used since I last saw you?’ as easily as ‘What’s your blood pressure?’ or ‘Tell me about your ankle pain.’”

Students also volunteer with syringe service programs, providing unused needles to people who inject drugs and collecting used syringes to reduce the spread of blood-borne diseases like HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.

By working with individuals who are in recovery as well as those who are not, these future health care providers are learning not only how to prescribe medication for OUD but also to how to look at patients holistically, Tourville explained. Many of those who have a substance use disorder are also dealing with issues such as homelessness, dental problems, counseling needs, childhood trauma, loss of custody of their children, and lack of transportation, she said.

“Our goal is to train health care providers who are knowledgeable and comfortable prescribing medications for OUD, regardless of their specialization, so that patients benefit from comprehensive care,” Tourville said, noting that physicians and nurses in all specialties can play a role in treating substance use disorder. “At the end of their time with us, we ask students, ‘What are you going to carry forward into your own practice?’”

Pharmacists Work to Reduce Stigma

Tyler Melton

Unfortunately, patients with OUD commonly face negative bias towards both their disease and their life circumstances, said Tyler Melton, assistant professor in the Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Translational Science and Rural Health Program coordinator at the UT Health Science Center College of Pharmacy. Melton is focusing his work on reducing stigma within rural community pharmacies by educating pharmacists about medications for opioid use disorder, discussing common issues they may face, and training them to understand the implicit biases and behaviors that contribute to stigmatizing environments for individuals seeking care for OUD.

Melton and fellow COURAGE team member Jarrod Vick, a pharmacist in Cocke County, are training pharmacists via an online learning management system that addresses the stigma pharmacists may exhibit toward patients with opioid use disorder, the origin of their biases, and the best ways to engage with patients.

“We are helping pharmacists realize the role they play in public health,” Melton said. “They are bastions of hope in these rural communities.” To date, three groups have successfully completed the training program, with 10 more pharmacists expected to do so this year.

After completing the online training, pharmacists come together as a group for a motivational interviewing workshop that allows them to role-play different scenarios they may encounter when treating patients with OUD. Melton calls the workshops the gem of the program, citing the success of team learning and the shared experiences the pharmacists develop.

Fifth Graders Focus on Prevention

It’s also important for those who work with youth to know how the adolescent brain is susceptible to substance use. That’s where Laurie L. Meschke, UT Knoxville professor of public health, is focusing her COURAGE work.

Laurie Meschke

“In one elementary school in our service area, over half of the students are living with caregivers who are not their biological parents—grandparents, foster care—and many times that is because of opioid use,” she said. “We know our young people have suffered a lot of trauma, and we know that when young people grow up with substance use disorder in the home, they are more likely to use drugs themselves.”

COURAGE has been working with fifth graders at a Union County elementary school to teach students about the dangers of OUD. All COURAGE facilitators are trained in both youth development and trauma-informed care, and the Youth HOPE curriculum developed by Meschke and her graduate students aligns with fifth-grade educational competencies such as reading for context, reading out loud, and vocabulary.

“Substance use disorder not only affects those who are experiencing it, but it has a ripple effect,” Meschke said. “If we can reduce the likelihood of adolescent substance use, we also can see reductions in other risk-taking behaviors such as sexual activity. We encourage youth to think into the future about who they hope to be and to identify obstacles that could get in their way.”

Meschke sees a lot of growth in the 10- and 11-year-olds over the course of the school year and has been impressed with students’ willingness to disclose the experiences they’ve had with their families.

“This speaks to the extremely personal nature of OUD,” she said, noting that fifth graders in the program have gone on to serve on a new youth advisory board at the local middle school. “We know what they’re learning can apply to their own lives and help youth support others.”

COURAGE goes beyond the classroom, providing in-service training opportunities for teachers and workshops for caregivers, all scheduled through fellow COURAGE member Mindy Grimm, director of ICARE–Union County.

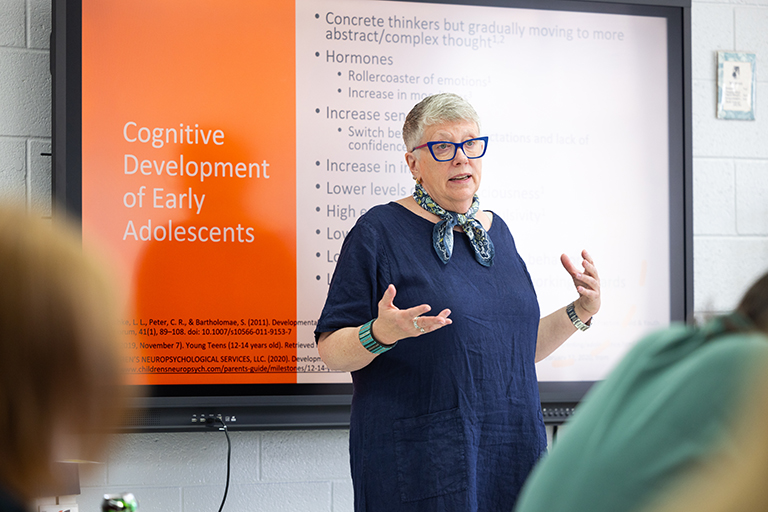

- Professor Laurie Meschke leads a session about early adolescent development for a group of middle school teachers during an inservice day at Union County High School

- Graduate student Su Chen Tan leads a session discussing how mental health impacts learning to a group of high school teachers during an inservice day at Union County High School

Because the topic of the workshops for caregivers always changes, COURAGE sees repeat attendees, Meschke noted.

“We focus a lot on developmental ages and stages,” she said. “We know that the adolescent brain is particularly vulnerable to addiction and that every year we can delay the initiation of substance use in young people, the better.”

Partnership Addresses Health Disparities

While COURAGE is focused on OUD challenges in rural counties, UT and Cherokee Health Systems are collaborating to address health disparities in Knoxville’s underserved populations through Research and Education Aligned for Clinical and Community Health, or REACCH.

The partnership brings together UT faculty, staff, and students and CHS providers to brainstorm new solutions to long-standing health issues in Knoxville and its surrounding counties. Its mission incorporates five points:

- To intentionally, strategically, and collaboratively conduct innovative interdisciplinary training and research to strengthen the health-related workforce

- To contribute to and disseminate an evidence base of health-related best practices

- To reduce health disparities

- To enhance health equity

- To advance the well-being of individuals, families, and communities across Tennessee

Hollie Raynor

REACCH is led by Hollie Raynor, executive associate dean of research and operations in the College of Education, Health, and Human Sciences at UT, and Eboni Winford, vice president of research and health equity at CHS. Raynor and Winford received $57,000 in funding from UT’s Office of Research, Innovation, and Economic Development.

While REACCH is new, UT and CHS have been working together for years, Raynor noted. For example, faculty and students in UT’s Department of Nutrition provide nutrition counseling to CHS patients and their families, because CHS does not have registered dieticians.

“In its infancy, the relationship was a faculty member saying, ‘Wow, we have this idea,’ or CHS saying, ‘We’ve got this need,’” Raynor said. “But we asked the question ‘Could we make something more formal, intentional?’”

Teams Focus on Type 2 Diabetes, Health Literacy

After REACCH released its strategic plan in November 2023, more than 50 UT faculty and CHS staff members expressed interest in developing and delivering new REACCH programs.

Raynor and Winford decided to support two teams: one concentrating on chronic disease, specifically Type 2 diabetes, and one focusing on health literacy. The teams bring together a vast array of expertise.

- UT faculty members and graduate students brainstorm new solutions in Type 2 diabetes treatment as part of REACCH

- Two UT faculty members discuss their efforts to improve health literacy as part of their collaboration through REACCH

The Type 2 diabetes team has 20 members with representatives from UT’s Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics; Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering; Min H. Kao Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science; Extension Family and Consumer Sciences; Department of Kinesiology, Recreation, and Sport Studies; Department of Mathematics; Department of Microbiology; College of Nursing; Department of Nutrition; Department of Public Health; and College of Veterinary Medicine. The health literacy team has six members with representatives from the CHS Continuing Education program and UT’s School of Design; Deaf Education and Special Education programs; Adult and Continuing Education program; and Center for Literacy, Education, and Employment.

Eboni Winford

“I was skeptical at first about including so many individuals from many different disciplines, but this is their opportunity to really co-create something instead of to contribute to someone else’s vision,” Winford said.

The teams started meeting in March to discover what each person brings to the table.

“Many of our faculty are in disciplines where they believe our research is supposed to enhance health, and many disciplines are also interested in how translation of research to practice can occur,” Raynor said.

REACCH Strives for Health Equity

Front and center are REACCH’s goals to reduce health disparity, which the REACCH team defines as “a type of preventable health difference that is closely linked with social, political, economic, and environmental disadvantage,” and to enhance health equity, “the state in which everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health.”

As a federally qualified health center, CHS provides services to children, adults, and seniors who have coverage through private insurance plans and state programs, as well as to those who have no health insurance. In 2023, CHS served 65,960 patients, more than 10,000 of whom were uninsured. Achieving health equity is more than helping patients overcome obstacles to health and health care, however. It requires ongoing societal efforts to address historical and contemporary injustices as well.

“Evidence-based guidelines for health care that are developed from research only work if the research is representative of the population that you are providing health care to,” Raynor said. “Most medical research has been conducted in populations generally not experiencing health disparities, so it may not be helpful as it doesn’t necessarily translate well.

“We have an opportunity here to develop a representative research base to better inform evidence-based health care guidelines that are effective for all—not just some—Tennesseans.”

UT Medical Center Offers Bridge to Outpatient Treatment

More than 300 people suffering from OUD have enrolled in treatment since January 2022, thanks to a program at the UT Medical Center that connects hospital patients with outpatient treatment centers before they step foot off the premises.

Julia van Zyl

“OUD is a community problem that deserves a community solution,” said Julia van Zyl, a hospitalist at UTMC, an associate clinical professor in UT Health Science Center’s Graduate School of Medicine, and one of the champions of the program. “We were seeing severe endocarditis on the [hospital] floors due to repeat injections of substances. Endocarditis is difficult to treat, but we see a lot of patients coming into the ER with repeat overdoses, so we thought, ‘Let’s get ahead of the problem and treat individuals before they develop endocarditis.’”

UTMC’s bridge program begins with providers asking patients if they want to seek treatment for their substance use.

“It’s important to know that these patients are people like you and me who are under the grip of powerful chemicals,” she said, noting that OUD usually starts with people in pain who get hooked on medication that is much more addictive than pain medicines of the past. “We are all pleasure-seeking people, and our brains make us want to feel good again.”

The program provides physicians with special training on how to initiate this conversation.

“We don’t judge these patients,” van Zyl said. “We offer them love and support. That’s the first pillar of our program.”

It’s also imperative, she stressed, that providers ask every patient every time.

“The next time could be their last time,” van Zyl said. “The fatality rate with fentanyl is so high. One gentleman overdosed and came to our ER 34 times, and the 34th time was the day he decided he was ready to change.”

Providers Offer Resources, Medication

If patients are not ready to seek treatment, UTMC providers offer community resources and safety supplies, and patients “take what they’re ready for,” said van Zyl.

“It’s not really that different than any of us,” she continued. “If you get a doughnut every time you pass a Krispy Kreme and then you find out your blood sugar is high, you still have to make the choice whether to stop and get that doughnut. All humans have to be ready to change.”

If patients indicate that they are ready to start treatment, UTMC providers interview them to assess their basic needs and identify any obstacles that would keep them out of recovery.

“A lot of the patients we see for substance use have lost family, jobs, income, homes, and health insurance because of their addiction,” van Zyl said. “We start out giving them a backpack with hygiene products, extra shirts, etc., but it’s not shocking that the top four things patients say they need help with are food, finances, transportation, and housing. If you’re at rock bottom and you don’t have anything to eat, you’re not going to prioritize your path to recovery.”

Next, providers prescribe opioid users with medication to treat their chemical dependency and withdrawal. This is medication UTMC can give patients that same day, which addresses their fight-or-flight response.

Peer Navigators Ease Transition

But the big difference in UTMC’s bridge program, van Zyl stressed, is partnering patients with peer navigators who are in recovery at McNabb Center—a nonprofit regional provider of substance abuse services—or Cherokee Health Systems. The peer navigators have been through what the patient is experiencing.

“I call our peer navigators the secret sauce,” van Zyl said. “Substance use can feel so shameful and stigmatizing that patients try to hide it, so early recognition by peer navigators is key.”

Peer navigators are on site at UTMC to help connect patients to care after they leave the hospital. Peer navigators from McNabb Center also can physically transfer patients who want to seek treatment to the McNabb Center, which has set aside one bed each day for the bridge program.

“If they say, ‘Yes, I want to start treatment,’ we have a very small window to treat them because a chemical has a hold of them,” van Zyl said. “We want that treatment to start the same day, so our peer navigators can transfer them to McNabb Center, which removes some of the anxiety. We have found that having that peer navigator with them to answer their questions like ‘Where is it? How do I get there? Who am I going to talk to?’ is a critical piece.”

One study shows that only 28 percent of patients show up to their first outpatient treatment appointment if written a prescription, she noted. By when peer navigators take patients from the hospital to the McNabb Center, 98 percent are showing up for their initial appointment.

“When we started the bridge program, there was a 21-day wait to start [outpatient] treatment,” van Zyl said. “The bridge program is successful because patients get same-day care.”

She estimates that peer navigators talk with between 250 and 300 patients each month—and every patient leaves with something. Of 545 patients who indicated they wanted treatment, 315 enrolled in the bridge program – a 58% acceptance rate.

“And at least nine months into the program, we see these individuals are returning to the ER 18 percent less and to the hospital 30 percent less,” van Zyl added.

UTMC follows patients throughout the program because physicians know it takes the frontal lobe of the brain two years to heal from opioid use. Following patients also lets UTMC know what parts of the program are working and what changes may need to be made.

And as for the gentleman who took UTMC up on its offer of treatment the 34th time he was asked?

“He has been in recovery now for over a year, and he’s back with his family and has a job,” van Zyl said. “This program has helped give him a new lease on life.”