In 1980, a group of recreational cavers discovered the first ancient cave art site in North America in the dark zones of caves located south of Knoxville, Tennessee.

Jan Simek, professor of anthropology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, recently explained the history and importance of this form of art in The Conversation.

Since the first discovery in 1980, archaeologists have found dozens of cave art sites in the Southeast. They have been able to learn details about when cave art first appeared in the region, when it was most frequently produced, and how it might have been used. Archaeologists have also learned a great deal by working with the living descendants of the cave art makers about what the cave art means and how important it was, and is, to Indigenous communities.

Cave Art in America?

Few people think of North America when they think about ancient cave art.

A century before the Tennessee cavers made their discovery, the world’s first modern discovery of cave art was made in 1879 at Altamira in northern Spain. The scientific establishment of the day immediately denied the authenticity of the site.

Subsequent discoveries served to authenticate Altamira and other ancient sites. As the earliest expression of human creativity—with some examples perhaps 40,000 years old—European Paleolithic cave art is now justifiably famous worldwide.

But similar cave art had never been found anywhere in North America, although Native American rock art outside of caves has been recorded since Europeans arrived. Artwork deep under the ground was unknown in 1980, and the Southeast was an unlikely place to find it given how much archaeology had been done there since the colonial period.

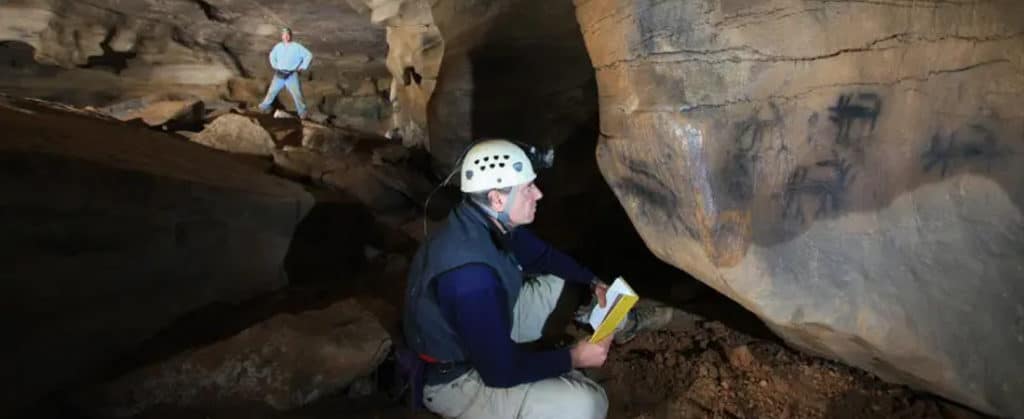

Nevertheless, the Tennessee cavers recognized that they were seeing something extraordinary and brought archaeologist Charles Faulkner to the cave. He initiated a research project there, naming the site Mud Glyph Cave. His archaeological work showed that the art was from the Mississippian culture, some 800 years old, and depicted imagery characteristic of ancient Native American religious beliefs. Many of those beliefs are still held by the descendants of Mississippian peoples: the modern Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Coushatta, Muscogee, Seminole, and Yuchi, among others.

After the Mud Glyph Cave discovery, archaeologists at UT initiated systematic cave surveys. Today archaeologists have cataloged 92 dark-zone cave art sites in Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. There are also a few sites known in Arkansas, Missouri, and Wisconsin.

What Did They Depict?

There are three forms of southeastern cave art:

- Mud glyphs are drawings traced into pliable mud surfaces preserved in caves, like those from Mud Glyph Cave.

- Petroglyphs are drawings incised directly into the limestone of the cave walls.

- Pictographs are paintings, usually made with charcoal-based pigments, placed onto the cave walls.

Sometimes more than one technique is found in the same cave, and none of the methods seems to appear earlier or later in time that the others.

Some southeastern cave art is quite ancient. The oldest sites date to some 6,500 years ago, during the Archaic Period (10,000–1000 BC). These early sites are rare and seem to be clustered on the modern Kentucky–Tennessee state line. Imagery was simple and often abstract, although representational pictures do exist.

Cave art sites increase in number over time. The Woodland Period (1000 BC–AD 1000) saw more common and more widespread art production. Abstract art was still abundant and less worldly. Probably more spiritual subject matter was common. Conflations between humans and animals, like bird–humans, made their first appearance.

The Mississippian Period (AD 1000–1500) is the last phase in the Southeast before Europeans arrived, and this was when much of the dark-zone cave art was produced. Subject matter is clearly religious and includes spirit people and animals that do not exist in the natural world. There is also strong evidence that Mississippian art caves were compositions, with images organized through the cave passages in systematic ways to suggest stories or narratives told though their locations and relations.

Cave Art Continued into the Modern Era

In recent years, researchers have realized that cave art has strong connections to the historic tribes that occupied the Southeast at the time of European invasion.

In several caves in Alabama and Tennessee, mid-19th-century inscriptions were written on cave walls in the Cherokee syllabary. This writing system was invented by the Cherokee scholar Sequoyah between 1800 and 1824 and was quickly adopted as the tribe’s primary means of written expression.

Cherokee archaeologists, historians, and language experts have joined forces with nonnative archaeologists like Simek to document and translate these cave writings. As it turns out, they refer to various important religious ceremonies and spiritual concepts that emphasize the sacred nature of caves, their isolation, and their connection to powerful spirits. The religious ideas reflected are similar to those represented by graphic images in earlier precontact time periods.

Based on all the rediscoveries researchers have made since Mud Glyph Cave was first explored more than four decades ago, cave art in the Southeast was created over a long period of time. The artists worked from ancient times when ancestral Native Americans lived by foraging in the rich natural landscapes of the Southeast all the way through to the historic period just before the Trail of Tears saw the forced removal of indigenous people east of the Mississippi River in the 1830s.

As surveys continue, researchers uncover more dark cave sites every year—in fact, four new caves were found in the first half of 2021. With each new discovery, the tradition is beginning to approach the richness and diversity of the Paleolithic art of Europe, where 350 sites are currently known. That archaeologists were unaware of the dark-zone cave art of the American Southeast even 40 years ago demonstrates the kinds of new discoveries that can be made even in regions that have been explored for centuries.

UT is a member of The Conversation—an independent source for news articles and informed analysis written by the academic community and edited by journalists for the general public. Through our partnership, we seek to provide a better understanding of the important work of our faculty.